Introduction to MFIs Part II: Microfinance Networks

April 25, 2017

This blog is the second in a series we are doing on microfinance. Before you read this, I suggest you see Part I Introduction to Microfinance Institutions (MFIs).

Here in Part II, I make an introduction to microfinance networks. What’s the difference between microfinance networks and microfinance institutions? Keep reading for an explanation.

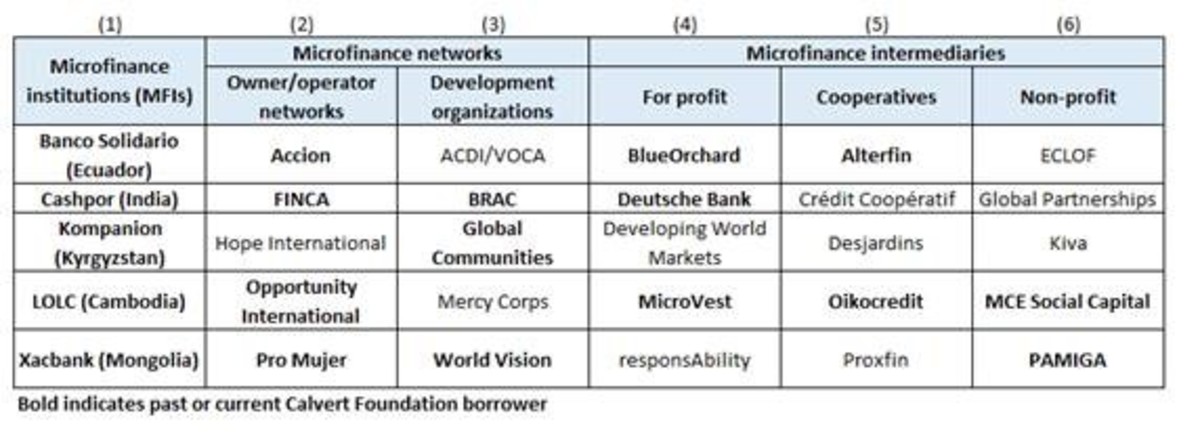

There are many different types of actors within the world of microfinance, from operating companies to investment companies to everything in between. Here at Calvert Foundation, we work with several different types of microfinance actors, which can be broken down into three categories: microfinance institutions, networks, and intermediaries. I’ve outlined some examples in Table 1 below. I wrote about column 1 in Part I. Today, I’ll be focusing on columns 2 and 3.

Table 1

What is a microfinance network?

Microfinance networks come in many shapes and sizes. The ones I’m talking about today have been categorized as “ownership plus” by a paper published by the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP). The term “ownership plus” means that the individual MFIs in a network are owned and sometimes founded by one parent organization. The easiest way to explain is to use a couple examples from our portfolio to show how microfinance became an approach to economic development adopted by both individuals and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the term typically used for U.S.-based non-profits that work internationally.

Owner/operator networks

Owner/operator networks are networks with microfinance roots. One of the best known owner/operator networks is FINCA. Originally an acronym for the Foundation for International Community Assistance, FINCA was started in El Salvador in 1985 by John Hatch, a former Fulbright scholar and Peace Corps volunteer. (For historical context, Grameen Bank in Bangladesh was started a year earlier in 1983. Many people had only first learned about microfinance when Grameen’s founder, Muhammed Yunus, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.) As with many international programs, FINCA was started with grant funding. In this case the funding came from USAID.

Today the FINCA network operates in 21 countries around the globe. They are headquartered in Washington, DC and have total consolidated assets of close to $1 billion. While each of the 21 MFIs has been developed based on the local context of the country where they operate, they are all branded with the FINCA name and benefit from the experience built up across the network over the past three decades. In his book, FINCA International’s President Rupert Scofield describes the lessons he learned along the way including the increasing coordination required as the organization grew and expanded.

Another owner/operator network is Pro Mujer, headquartered in New York City with total assets of $161 million. They were started in Bolivia in 1990 by two school teachers, Lynne Patterson, an American, and Carmen Velasco, a Bolivian, as a women’s development program funded by grants from USAID and the Bolivian government. Today their work spans across five countries in Latin America and they remain focused on serving women. Their model also includes auxiliary services for their members, such as healthcare and health insurance.

Development organizations

Not all microfinance networks have their roots in providing loans however. Sometimes, they evolve within larger organizations that started out doing other types of development work.

The development and humanitarian organization World Vision was founded in 1950 at the start of the Korean War to work with Korean orphans. In the 1960s, World Vision grew to provide humanitarian aid after natural disasters and in the 1970s shifted to a broader development model. They experimented with community-owned loan funds in the 1980s and started supporting MFIs in the 1990s. Headquartered in Monrovia, CA, the World Vision network consists of more than 30 MFIs with consolidated total assets of $440 million.

Another example of a development organization that evolved into a microfinance provider is Global Communities. Founded in 1952, they initially had a mission to build cooperative housing in the U.S. (their original name was the Cooperative Housing Foundation). In the 1960s, USAID asked them to use their expertise to help develop low-income housing in Latin America. By the 1980s Global Communities focused exclusively on international operations and started providing home improvement loans, which later seeded their microfinance programs. Today they have microfinance operations in eight countries.

Non-profit owners of for-profit holding companies

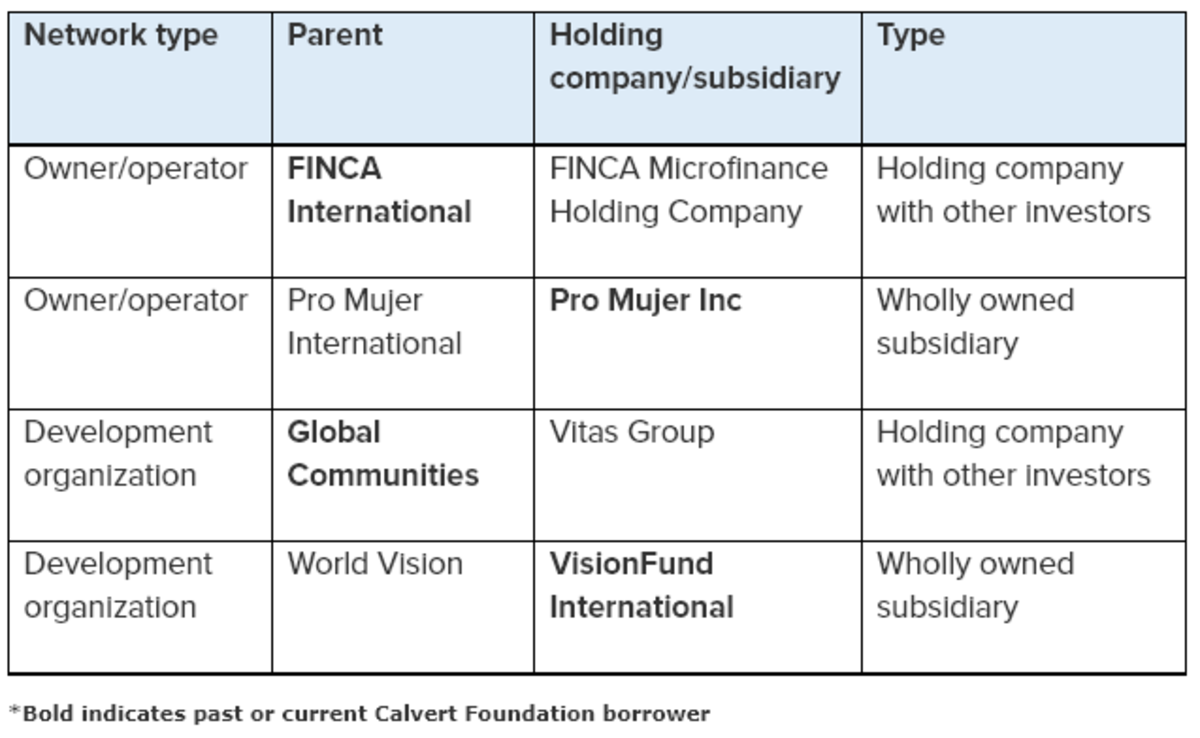

FINCA, Pro Mujer, Global Communities, and World Vision are all non-profits that have created separate entities to house and manage some or all of their MFIs (see Table 2 below). These separate entities were created to either primarily manage or primarily fund their microfinance operations. FINCA and Global Communities created for-profit holding companies to allow their MFIs to grow through socially responsible investment rather than depend solely on donor funding. As for-profits, they can sell equity in addition to borrowing debt. Non-profits cannot raise equity. In 2011, FINCA created FINCA Microfinance Holding Company with partners such as the International Finance Corporation (part of the World Bank Group), making a combined equity investment of $74 million. Global Communities is the founder and majority owner of the Vitas Group, a holding company created in 2006 (then called CHF Development Finance) to own and manage its commercially oriented MFIs. Vitas sold a minority share to Bamboo Finance (then called BlueOrchard Private Equity Fund) for $1.6 million.

Table 2

World Vision and Pro Mujer created non-profit subsidiaries. World Vision created Vision Fund in 2003 when the size and complexity of their microfinance operations across 35 countries required a specialized organization to manage them. Pro Mujer also has a non-profit subsidiary that owns several of its MFIs.

In conclusion

In each of these examples, microfinance began as a donor-funded program. As the programs grew, they professionalized operations and began leveraging more commercial capital to scale which sometimes required creating new structures to channel that capital. Their focus was on investors whose values aligned with their work.

To learn more about these microfinance networks I encourage you to visit their websites. If you’d like to support their work with an investment that earns both a financial and social return, you can invest with Calvert Foundation, starting from $20 online.

Stay tuned for Part III of this series, in which I will be focusing on microfinance intermediaries, outlined in column 4 and 5 in Table 1 above.

Ready for the next post? See Post III.